Designs for Living With Art

Rainey Knudson

CANVAS, September, 1998

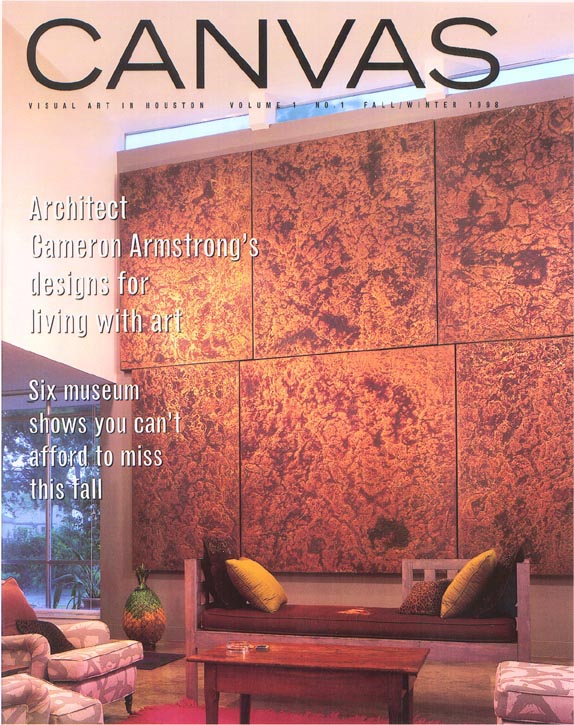

"Want to... build a home around your art collection (or have a home that begs a collection be built)? Tired of trying to refrigerate a house designed for winters in the French Alps? Meet architect Cameron Armstrong, whose metal homes The New York Times has called Houston's 'great shining hope.' "

Cameron Armstrong's aluminum-clad houses are not the first in Houston; in fact the West End has a tradition of metal homes going back to the 1960's. But Armstrong makes metal with a twist: the shiny structures are often designed around important collections of art. "He builds these baby museums

that are completely liveable and have this reflective surface like a jewel," says Stephanie Adolph, another Houston architect. Armstrong's homes have spearheaded the resurrection of the West End, a once-sleepy neighborhood now known as Houston's SoHo. Suzanne Dungan (whose house is pictured on the cover) says she initially became enchanted with Armstrong's work for his sense of volume and light as well as his understanding of the display of art. Building for art is important for Armstrong -- his wife Terrell James is a painter, and the couple's home is filled with their own art collection. But Armstrong's designs are practical as well as aesthetic. Not only do they gracefully house art; they also cut their owners' electricity bills dramatically. The metal skin of Armstrong's homes is renowned for its efficiency in this climate, acting like a Thermos to deflect heat and cool instantly with passing clouds. And surprisingly, the metal is inviting and even beautiful -- it glows and changes color throughout the day. So if the thought of living in a soulless reproduction Tudor leaves you cold, a metal house by Armstrong might be the answer. CANVAS' Rainey Knudson talked with this Yale-trained architect about the collision between architecture and art.

Rainey Knudson: What was the first work of art you ever bought?

Cameron Armstrong: Well, in college if you became a friend of the museum they'd give you a print. Every year it was an original numbered edition by a well-known artist. And I can remember getting this print and leaving it rolled up for years.

Rainey Knudson: Who was the artist?

Cameron Armstrong: John Chershy. I would take it out from time to time and look at it, and finally I decided to get it framed. This piece that at first I respected because I was told to, I gradually learned to appreciate for its beauty-which I had not seen at first-and suddenly I found that the history of my coming to appreciate it was valuable. So I wanted to frame it both for the work itself and so I could have it on my wall to remember how I came to see its beauty.

Rainey Knudson: How old were you when you had it framed?

Cameron Armstrong: I got that work when I was about 19 and had it framed when I was 30. I had it a long time before I realized the value of the work and the real value of my coming to appreciate it. So when I look at it, I appreciate the process of looking at art that continues-and the fact that now I don't really think it's that great a piece.

Rainey Knudson: Well that happens. You outgrow art.

Cameron Armstrong: Oh yeah. And there's nothing wrong with that.

Rainey Knudson: So how do you go about looking at art nowadays?

Cameron Armstrong: Well, you have to get an intuitive gut feeling. I had someone call me up a while ago who was considering buying a very expensive sculpture, and he felt kind of pressured to buy it because he knew it was a great piece, and he knew everybody knew it. And he appreciated it intellectually, but his relationship with it just didn't sing-and I said listen, if this doesn't excite some kind of passion in you, you should walk away from it immediately. It's not worth the anxiety.

Rainey Knudson: Have you ever had trouble trusting your instincts about art?

Cameron Armstrong: All the time. But I'm comfortable now with looking at art and the question of whether I trust my own eye. When I see a work I like, I try to borrow it for a while until I decide. I think looking at art towards collecting it and living with it requires practice. I hate to say it's work, but it requires energy. And sometimes I see something that I think doesn't look like artwork, and I tend to think that maybe it's just too sophisticated for me.

Rainey Knudson: But sometimes it's just bad art.

Cameron Armstrong: Yes, you don't want to get into the state where you can't reject anything. You must take a position. But it's gotten to the point where bad art can be fascinating, because of the question of why it is bad, and how far off it is. If the artwork's easier- If it's easier, then what's the point? It's pretty, it's easy, it passes right by. Pieces of work that are a problem for me tell me something about myself. When I feel challenged by a piece of art, I know that it's actually working at me on some unconscious level.

Rainey Knudson: So what about building for people's art collections?

Cameron Armstrong: Well, I've had to build for specific pieces like Michael Tracy's Smoking Mirror (pictured on the cover). It's a large work; it covers a wall that's about 18 by 17 feet. And Tracy's work is very intense, so the design of the house had to respond to it. The work that I do is actually very light, which means that rooms are defined not by walls or doors per se, but by the end of a particular plane of light or the casting of a shadow. So that type of design could be vulnerable to the artwork. In that house, there was a question of whether the painting would overwhelm the living room and just make the whole house go up in a puff of smoke.

Rainey Knudson: How did you deal with that?

Cameron Armstrong: I designed a large steel fireplace for the opposite wall. The fireplace's structure and color make a strong statement that balances the artwork.

Rainey Knudson: What do you think is the most important part of designing buildings?

Cameron Armstrong: Well, architecture is not supposed to take you away from the present time and place, it's supposed to bring you into a greater experience and awareness of the present and of the people you're with. And for me that's what building is all about. It's funny-when we moved into our house, Terrell and I suddenly found the quality of our conversation improving.

Rainey Knudson: Really.

Cameron Armstrong: Yes. And that's very different from most places being built. The so-called traditional kinds of motifs are speaking a retail language that eliminates the possibility of attention to things like light and nature and other people.

Rainey Knudson: So what do you think about architecture in Houston? Like, compared with other places...

Cameron Armstrong: Well, Houston likes to see itself as resolutely objective, whereas in Los Angeles fiction is a birthright. Personally, when I go to L.A. I don't really object to those fake Spanish houses or those fake French houses, because they're just another fiction and will do just fine if you only just water the grass. In Houston, fiction that is just fiction is something you might get arrested for... just kidding.

Rainey Knudson: I think there's actually a lot of fiction here.

Cameron Armstrong: There is, but it's not convincing as fiction per se. You compare a fake French chateau in Houston to a fake French chateau in L.A., the one in L.A.'s much closer to seeming real. They look like cardboard here. Basically, people here aren't serious about appearances beyond how they might help sell their politics or their real estate, pretty much the same thing, and that's a matter of alternate realities, not alternate fictions. Compared to the advantages that come with simply dismissing objective reality, designing in and for the present moment doesn't offer very much value. Basically, whatever marketing they can easily buy, they buy; beyond that, they don't believe design makes a difference.

.... for Armstrong, living with art and light and volume makes all the difference.