go to... New York Times

Homes of Metal: Great Shining Hope?

By Donna Paul

New York Times, May 14, 1998

FROM the air, the West End of Houston blazes below, an unearthly apparition. It's not just the roofs that are glinting: it's the houses. In this neighborhood, some are clad entirely in metal

Sitting

quietly, luminous and sleek in the 95-degree vapors, they seem at once

warm and elegantly cool. This is the magic of metal, and though it may

not be for everyone, it is a brave new front for homes.

Building with metal combines futurist fantasy with down-home practicality.

Metal farm sheds and barns have dotted the American landscape for generations,

as have sturdy industrial buildings. And throughout the South, the hot

tin roof is ubiquitous. But over the last few years, architects who blend

vernacular imagery and contemporary thinking -- firms like Will Bruder

in Phoenix, Lake Flato in San Antonio and Cameron Armstrong in Houston

-- are building houses that may elevate metal to residential art.

Mr. Armstrong, a Houston architect, has almost literally turned the idea

of metal housing on its side. The roofs of his houses are made of conventional

shingles, which he says are easier to repair; the skin of the house is

Galvalume, a fuss-free metal too versatile to limit to industrial uses.

"The modern house may have found its exterior material,'' said Mr. Armstrong, who considers the metal " a way to finally have a material that is as advanced as its design."

Galvalume, made by BIEC International Inc., of Kalama, Wash., is steel

coated with zinc, aluminum and silicon to make it more durable and resistant

to rust. It has been used since the 70's, but primarily for industrial

buildings.

He became fascinated with sheet metal as a material while a student at

the Yale University School of Art and Architecture in the early 80's.

But it wasn't until he moved here that he thought of it for residential

design. Living in the West End, a neighborhood whose architectural vernacular

was an unusual collection of metal industrial buildings and clapboard

cottages, inspired him. ''It took me a long time to see its obvious beauty,

but once I saw it in sunlight and it glowed, I was hooked,'' he said.

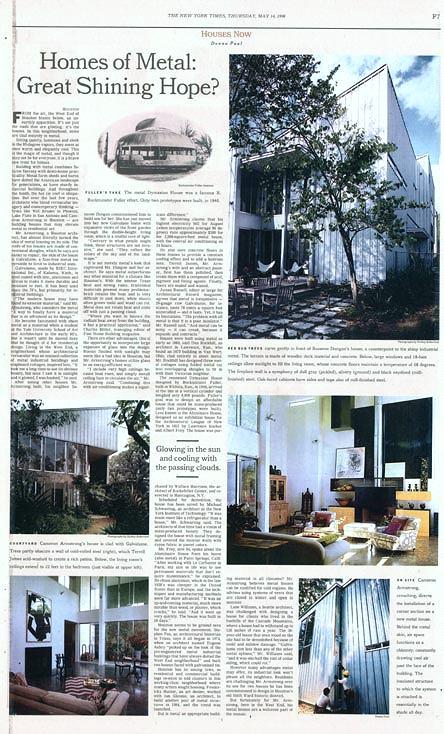

After seeing other houses Mr. Armstrong built, his neighbor Suzanne Dungan

commissioned him to build one for her. She has just moved into her new

Galvalune home with expansive views of the front garden through the double-height

living room, which is a soulful core of light. ''Contrary to what people

might think, these structures are not invasive,'' she said. ''They reflect

the colors of the sky and of the landscape.''

It is not merely metal's look that captivated Ms. Dungan and her architect.

He says metal outperforms any other material for a climate like Houston's.

With the intense Texas heat and strong rains, traditional materials present

many problems: brick retains the heat and is very difficult to cool down,

while stucco often grows mold and wood can rot. Metal does not retain

heat and cools off with just a passing cloud. ''Where you want to bounce

the radiant heat away from the building, it has a practical application,''

said Charles Miller, managing editor of Fine Home Building magazine. There

are other advantages. One is the opportunity to incorporate large expanses

of glass into the design. Rooms flooded with sunlight may seem like a

bad idea in Houston, but Mr. Armstrong's homes utilize glass in an energy-efficient

way.

''I include very high ceilings because heat rises, and simply install

ceiling fans to circulate the air,'' Mr. Armstrong said. ''Combining this

with air-conditioning makes a significant difference.'' Mr. Armstrong

claims that his highest electricity bill for August (when temperatures

average 96 degrees) runs approximately $200 for his 2,500-square-foot

metal house, with the central air conditioning on 24 hours. He also uses

concrete floors in these houses to provide a constant cooling effect and

to add a lustrous note. Terrell James, Mr. Armstrong's wife and an abstract

painter, first has them polished, then treats them with a compound of

acid, pigment and fixing agents. Finally, floors are sealed and waxed.

James Russell, editor at large for Architectural Record magazine, agrees

that metal is inexpensive -- 26-gauge raw Galvalume, for instance, costs

70 cents a square foot uninstalled -- and it lasts. Yet, it has its limitations.

''The problem with all metal is that it is a poor insulator,'' Mr. Russell

said. ''And metal can be noisy -- it can creak, because it expands and

contracts.''

Houses were built using metal as early as 1860, said Dan Rockhill, an

architect in Lawrence, Kan., who found an 1875 building in Van Wert, Ohio,

clad entirely in sheet metal. Mr. Rockhill has designed three metal cottages

using folded metal cut into overlapping shingles to fit in with their

Victorian neighbor. The renowned Dymaxion House designed by Buckminster

Fuller, built in Wichita, Kan., in 1946, arrived at the site in a vertical

cylinder and weighed only 6,000 pounds. Fuller's goal was to design an

affordable house that could be mass-produced (only two prototypes were

built). Less known is the Aluminare House, designed as an exhibition house

for the Architectural League of New York in 1931 by Lawrence Kocher and

Albert Frey. The house was purchased by Wallace Harrison, the architect

of Rockefeller Center, and re-erected in Huntington, N.Y. Scheduled for

demolition, the house has been saved by Michael Schwarting, an architect

at the New York Institute of Technology. ''It was made more like a refrigerator

than a house,'' Mr. Schwarting said. The architects of that time had a

vision of mass-produced beauty. They designed the house with metal framing

and covered the interior walls with rayon fabric in pastel colors.

Mr. Frey, now 94, spoke about the Aluminaire House from his home (also

metal) in Palm Springs, Calif. ''After working with Le Corbusier in Paris,

my aim in life was to use permanent materials that don't require maintenance,''

he explained. He chose aluminum, which in the late 1920's was cheaper

in the United States than in Europe, and the techniques and manufacturing

methods were far more advanced. ''It was an up-and-coming material, much

more durable than wood, or plaster, which cracks,'' he said. ''And it

went up very quickly. The house was built in 10 days.''

Houston seems to be ground zero for the new metal movement. Stephen Fox,

an architectural historian in Texas, says it all began in 1974, when an

architect named Eugene Aubry ''picked up on the look of the pre-engineered

metal industrial buildings that have always dotted the West End neighborhood''

and built two houses faced with galvanized tin. Houston has no zoning

laws, so residential and commercial buildings co-exist in odd clusters

in this working-class neighborhood where many artists sought housing.

Fredericka Hunter, an art dealer, worked with Ian Glennie, an architect,

to build another pair of metal structures in 1984, and the trend was launched.

But is metal an appropriate building material in all climates? Mr. Armstrong

believes metal houses can be modified for cold regions. He advises using

systems of vents that are closed in winter and open in summer.

Lane Williams, a Seattle architect, was challenged with designing a house

for clients who lived in the foothills of the Cascade Mountains, where

a house had to withstand up to 120 inches of rain a year. The 30-year-old

house that once stood on the site had to be demolished because of mold

and mildew damage. ''Galvalume cost less than any of the other metal options,''

Mr. Williams said, ''and it was one-half the cost of cedar siding, which

could rot.''

However many advantages metal may offer, its industrial look won't please

all the neighbors. Residents are challenging Mr. Armstrong over its use

for two houses he has been commissioned to design in Houston's old Sixth

Ward historic district. But fortunately for Mr. Armstrong, here in the

West End, his metal houses are a welcome part of the mosaic.