UN-ZONED: A MEMOIR

Cameron Armstrong

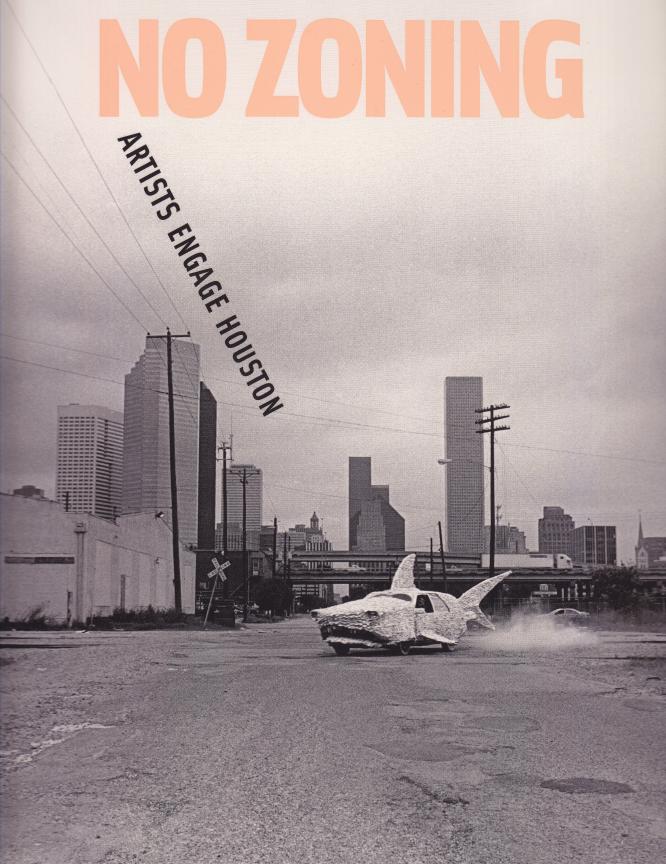

For five months during 2009, the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston hosted a massive survey of work by artists devoted to engaging the city on its own terms, and at its own scale. No Zoning, curated by Toby Kamps, focused on both historical documents, and pieces created especially for the exhibition. Cameron's essay for the accompanying catalog (amazon.com) described the history of Houston's site works, and provided a guide to their role in its mythology and emerging form. For more information, follow the links above, and consult the No Zoning catalog (released October, 2009).

At the beginning of 1993, by what seemed a series of accidents, I found myself in the middle of the latest (and probably last) of Houston’s five attempts to impose a top-down, legislated order on its famously unruly urbanism. At the time, the city had only just begun to recover from the decade-long depression following the oil economy’s collapse. For a variety of reasons, including dissatisfaction with previous development and fears of chaos should construction resume, a comprehensive land use ordinance, a.k.a. zoning, seemed a strong possibility. As a commercial real estate broker, sometime expert on zoning elsewhere (New York), an architect, a property owner in a neighborhood deemed by the City of Houston to be “un-zonable,” and someone related by marriage to die-hard zoning critics, I found myself ringside at the heated debate over the new law. More than that, by the end of January I had been cajoled into helping my little neighborhood write its own “special district ordinance” to be enacted under the aegis of the overall plan.

The West End, named for the trolley line once connecting it with downtown, is bounded by Washington Avenue on the north, Memorial on the south, and Durham and Westcott to the east and west. Much of it had originally been part of the village of Brunner, the first area platted outside Houston’s ward system. Early residents, often newly arrived from Central Europe, had built ranks of dignified cottages in a patchwork of small subdivisions between 1900 and 1930 (including “Rice Military,” as the area is now often called). Later, as Houston grew and their children relocated to the suburbs, the West End welcomed new immigrant communities, mostly Hispanic. A cluster of African American families, whose tenure predated most others, remained in its heart. By 1995, the neighborhood's low rents and exotic charm had also attracted museum directors Walter Hopps and Linda Cathcart, curators Caroline Huber, Janet Landay, Bertrand Davezac, and Cecily Horton, and artists such as Terry Andrews, Bobbie Bennett, John Berry, Sharon Berryman, Karin Broker, Dick Craig, Roy Fridge, Jim Groff, Dan Havel, Terrell James, Jim Love, Rick Lowe, Andy Mann, Kirk McCarthy, D. A. McNulty, Kathleen Packlick (and her West End Gallery), Kate Petley, Dean Ruck, Trudy Sween, Jackie Tileston, Nestor Topchy, Tricia Tusa, Randy Twaddle, Sharon Wilcutts, Dick Wray, Peter Yenne and Frank Zeni. Nearby were other artists, like the Art Guys and Frank Martin, and the art galleries of Hiram Butler (now Devin Borden Hiram Butler Gallery) and Fredericka Hunter (Texas Gallery).

But whatever its artist and gallery density, the West End was in most respects typical of nearby inner city neighborhoods. Sandwiched between major business centers, established residential areas, and tracts primed for large-scale development, few such areas had seen much of Houston’s postwar prosperity. As backwaters in the city’s boom, they had become host to numerous marginal business and residential communities. Nor did they conform in any obvious way to the future imagined by the new zoning ordinance. The West End Special District Ordinance and similar attempts to customize the new law emerged from this misfit. These initiatives inevitably created disagreement and tension as planners tried for regulations that would balance differences rather than enforce conventions. Some in the contentious process of crafting the West End's specialized regulations demanded unfettered rights for business, while others wanted new construction limited to single-family homes. Yet others fought to protect historic architecture, or assure cheap property for immigrant homesteads. The artists found their own voice in visions of studios and art parks. All feared the massed subdivisions and malls of developers’ dreams, but few wanted to stop construction outright. Hopes for change (and redevelopment) were explicitly opposed to fantasies of preservation. As might be expected in a city riven by extremes of stability and growth, yet dedicated to both, the debates were fought on implicitly cultural grounds, touching deep expectations about home and community. Passions ran high. Although zoning ultimately failed by referendum, its microcosm in such debates was a crucible of self-consciousness throughout the inner city. In the minds of some artists, these neighborhoods and their small buildings must suddenly have appeared in a new light, as art materials in themselves. What remained was to put those materials to use.

Such ideas were not entirely new, and certainly not to 1990’s Houston. Nationally, site-specific sculpture was well established: artists like Gordon Matta Clark, Michael Heizer and Richard Serra had long since pushed deep into the landscape. As early as the 1960’s, local folk artists like Jeff McKissick with The Orange Show and John Milkovisch with the Beer Can House had launched paradigms of expressive shelter. During the 1970’s and '80’s, this tradition was carried forward by Cleveland Turner (“the Flower Man”), among others. The appearance of Dan Havel’s Alchemy House (1993–94), Jim Pirtle’s Notsuoh (1996–ongoing), and other site works echoed this individualist spirit, but also addressed the paradoxes attending communal memory in a place radically devoted to dynamic growth and civic reinvention. Unlike either the folk monuments or previous artistic works, these projects did not simply memorialize extraordinary visions. Instead, moved by a do-it-yourself spirit, their authors dedicated a synergism of sculpture, architecture, and performance to social construction. Exploiting disused properties, low property values, and the boundless permissions of a city un-zoned by either laws or proprieties, they engaged Houston on its own terms, and at its own scale.

This migration to neglected areas carried strong echoes of regional history. Like the pioneers, the artists often cooperated in clearing each others’ property and erecting rustic shelters—although now in disused warehouses rather than wilderness clearings. Like the builders of Houston’s railways, ship channels and airports, they sought large government grants. But their approach to “‘undeveloped’” land (and neighborhoods) was new, and quite different. The little villages along Washington Avenue, parts of Houston Heights, and areas to the east and south of downtown had long been overlooked by mainstream entrepreneurs, and were up for grabs. To the artists, these voids in the economic geography offered an inverted, looking-glass version of the homogenized desires and products of conventional development. With an ethos echoing land brokerage as much as art, they saw raw material for large-scale works in these neighborhoods’ undervalued properties and improvised infrastructures of casual industry and familial networks. Borrowing and squatting their way towards legal tenure, they turned warehouses and humble dwellings first into cooperative studios, and then into spaces for theatrical and artistic performance. Vacant tracts and old houses were transformed from scenes of abandonment into venues for new symbolic geographies. Any step in constructing a site work could take on ritualized significance—even the processes of negotiating ways through (and around) the building codes could fulfill a Duchampian aesthetic of performance. With a vivid sense of being “un-zoned,” the artists recast close-knit neighborhoods of small churches, corner stores, shared gardens, and family ties into the means by which authentic community could be recovered and celebrated as social sculpture.

The range of this work was as broad and deep as the cultural and spiritual voids it symbolically reversed. At Main Street’s Notsuoh, Jim Pirtle had recognized a human-scale apotheosis of the Cornellian box in a fossilized, defunct retail space (complete with sales slips and thousands of shoes). The bar, coffee shop, and performance spaces that emerged were soon colonized by artists, misfits, and business people, their drinking and chess serenaded by the in-house band Free Radicals. In celebratory parades and performances like The Art Guys Blow Through Town (1995)—with leaf blowers!—and in ritualized deconstructions like Dan Havel’s Alchemy House, others claimed the entirety of the city as both site and medium. In a Third Ward block of shotgun houses, Project Row Houses transformed artist collaborations and an emergent venue for installation into a progressive model of community. These works expressed the conflict between the corrosive reality of Houston’s dehumanizing scale and hectic redevelopment, and human needs for stability and meaning. Nested in the tensions between solid object and ephemeral performance, they created an art of place in which an aesthetic of community could supercede the soulless economics driving their mainstream twins, the “complexes,” “plazas,” and “mansions” of conventional success.

It’s easy to see why the proposed zoning ordinance was equally toxic to certain artists and developers. The commitment to a deregulated imagination that led West End artists like Jim Love and Karin Broker to oppose rules mandating the construction of suburban-style “starter homes” was not so different from the spirit that inspired Meredith James, co-founder of the ordinance-slaying Houston Property Rights Association (and my cousin by marriage), to declare, “Zoning ... a Mortal Sin (‘Thou Shalt Not Covet Thy Neighbor’s Property’).” Developers and artists alike reveled in the city’s tacit and explicit permissions to destroy or appropriate whatever value they could identify. But the politics of this common cause also had a “through-the-looking-glass” quality, since with the Special District Ordinance the artists hoped to preserve rather than overcome what Walter Hopps had called the West End’s “funky reality.” In the end, neither artists nor developers got to see whether zoning would sustain or destroy the liberties they imagined. Certainly, with its defeat, chances for preserving the area’s diverse complexity were doomed, along with its historical assemblage of wooden cottages. But so were opposing hopes for suburban subdivisions. Ultimately, a strong market for medium-density ‘town houses’ would sweep through the neighborhood and literally carry it off: hundreds of little houses were trailered away or destroyed in the ensuing decade, as were the last remains of 1917’s mutinous Camp Logan and ultimately some of the West End’s key site works, including Nestor Topchy’s Templo (1996–2001) and O House (1995) by Dan Havel, Kate Petley, and Dean Ruck.

The debates over zoning and the ordinance’s defeat had preserved the developers’ unrestrained license, awakened the artists, and pushed into sharp relief the absences embedded in Houston’s sprawling approach to city-building. These voids had emerged not only in its economic geography, but throughout the fabric of urban life. Awash in speeding automobiles, parks and city streets had lost their power to anchor personal symbologies. Dwarfed by freeways and massive towers, the axes and squares of old-fashioned city planning could have little impact on visual order, or much grip on civic experience. Traditionally-scaled mainstays of civic memory, whether bronze figures raised on pedestals, men on parade, or site-specific messages inscribed in building facades, were literally lost amongst vast expanses of subdivisions and strip malls; only in epic form, as with rodeo trail rides, could human scale claim the foreground. But the defeat of time-honored ways of joining people to their city pointed neither to inherent flaws nor to the obsolescence of underlying human needs. The very success of Houston’s culture of rampant growth had itself created this failure, by denuding the landscape of the intimacy in which these methods could function. Only in forgotten backwaters like the West End was memory still embedded in buildings, society still engaged with place.

Echoing the auto industry’s use of identical chassis for multiple models, Houston’s real estate developers typically erect similar buildings and combinations of buildings, differentiated only by “design themes,” for the sake of common architectural, infrastructure, and financial designs. They have come to depend on the ability to achieve a simple, seamless integration of financial capital with large tracts of readily accessible land, all structured around predictable patterns of market demand and economic concentration. Therefore, whether working as a single huge enterprise or as many small players, they were unable to easily extract value from poor, complex neighborhoods like the West End. Uncertain land titles, improvised utilities, and persistent social problems put these otherwise available and well-located areas out of operational reach. As a result, the West End and its cousins were systematically neglected during the the boom years of the 1960s and '70s, and ultimately subjected to extreme stresses of poverty and decay. However, for the artists, this impoverishment had the perversely positive effect of maintaining the low land costs needed by big art projects, and preserving the communities that served them as both sites and subject matter. Investment-starved but rich in history, these areas begged comparison with the cultural voids of successful mainstream 'complex' and ‘strip’ developments. The very strangeness of their use as venues for recovering an active, civil urbanity commanded a powerful foreground for the works they came to host. Paradoxically, the magnitude of the mainstream’s success, of which its inability to assimilate small, depressed backwaters was the flip side, had produced in them a parallel, marginal world, where the spiritual emptiness of the city’s urbanism could be ritually exorcised.

The usual response of land men to forgotten remnants of previous booms—that is, to “bottom feed” and assemble likely properties, and then spin them into new rounds of speculation—can seem cannibalistic when considered in terms of the greater civic good: it’s not intuitively obvious that destroying established communities for the sake of short-term (re)development is a good thing. Destruction was also part of the artists’ vocabulary, and there is a parasitic element in works piggybacked on neighborhoods’ dissolution, such as the serial appropriation of soon-to-be-demolished buildings by Dan Havel and Dean Ruck . In principle, the artists’ exploitation of the city’s broad freedoms in their transformation of cheap, available properties, and even whole neighborhoods, can seem little different from the workings of the official real estate economy. Certainly, their libertarian ethos was no less rooted in Houston’s myth of the entrepreneurial pioneer. Sifting through the detritus of cycle after cycle of boom and bust, both artists and developers instinctively saw in these debris the foundations of new value.

The process of negotiating the West End Special District Ordinance forced the entire neighborhood to confront its prospective redevelopment, recognized as inevitable with or without zoning. My role as interpreter was predicated on competence with such regulation, belief in its positive potential, and a position astride the stake-holding communities. However, as I discovered the ways in which the new law would constrain unconventional uses and new site works, to say nothing of my own hopes for contemporary architecture, I came to respect Houston’s traditional liberties. Like everyone in the neighborhood, I was compelled to rethink my work (in design and real estate), my loyalties (to artists, neighbors, and realtors), and my agreement (or disagreement) with family advocates of the free market. Professionally, I was thoroughly implicated in the machine of redevelopment, yet personally I was drawn to the consolations provided by art’s deeper focus. The differences refracted in the prism of zoning politics were divisions also emerging naturally within my own view of Houston and its future. Certainly, there was much to dislike about the city’s disordered state: the mishmash of uses and scales, the jarring breaks in landscape and utility. But by the peak of zoning’s political campaign, consistency had begun to seem a poor trade for liberty, and the vitality it guarantees. The tragedy of the West End was that the freedoms necessary for its site works would also assure their destruction in the next round of speculation. Since then, events have shown mainstream development to be as corrosive as ever to the social, spiritual, and cultural needs of urban life. Negatively, one could point to a never-ending circle of decay and demolition, producing little of lasting value. An optimistic view is that, un-zoned, Houston will continue to cast up doppelgangers of its formless growth, reverse self-images performing its deeper necessities. Regardless, like my own involvement in the zoning struggle, the city's future seems foretold in past relations. Nowadays, our way of making and remaking it seems to me simply an exhaustive research into what can be removed and what added. The results, whether suburban tracts or soulful artworks, seem not accidental at all, but rather the inevitable lifework of Houston, the emergent city, a place where anything can happen, and everything eventually will.